A few weeks ago, I was invited to write a personal perspective for my former magazine—on any topic of my choosing. The request arrived just after a brief but intense immersion in the world of extroverts, and I was craving solitude. The article was published on September 18, 2025, in Serbian language. This is its essence.

There is a lingering stigma around introvert personality traits, especially in extrovert-driven environments.

Some progress has been made in the past decade, mostly in how we perceive ourselves—we’re no longer hesitant to identify as introverts. But we’re still waiting for the other side—our noisy, chatty, and “mighty likable” brethren—to recognize the strength of our quietness in a world that never stops talking. Regardless of where you fall on the spectrum, I highly recommend Susan Cain’s 2013 book Quiet, whose title I’ve just paraphrased.

It’s estimated that 30% to 50% of people are introverted. As a laywoman—and perhaps because I’m surrounded by introverts—I lean toward the higher estimate. We’re not a fringe group; we make up half of humanity. Yet introversion is still often seen as a flaw.

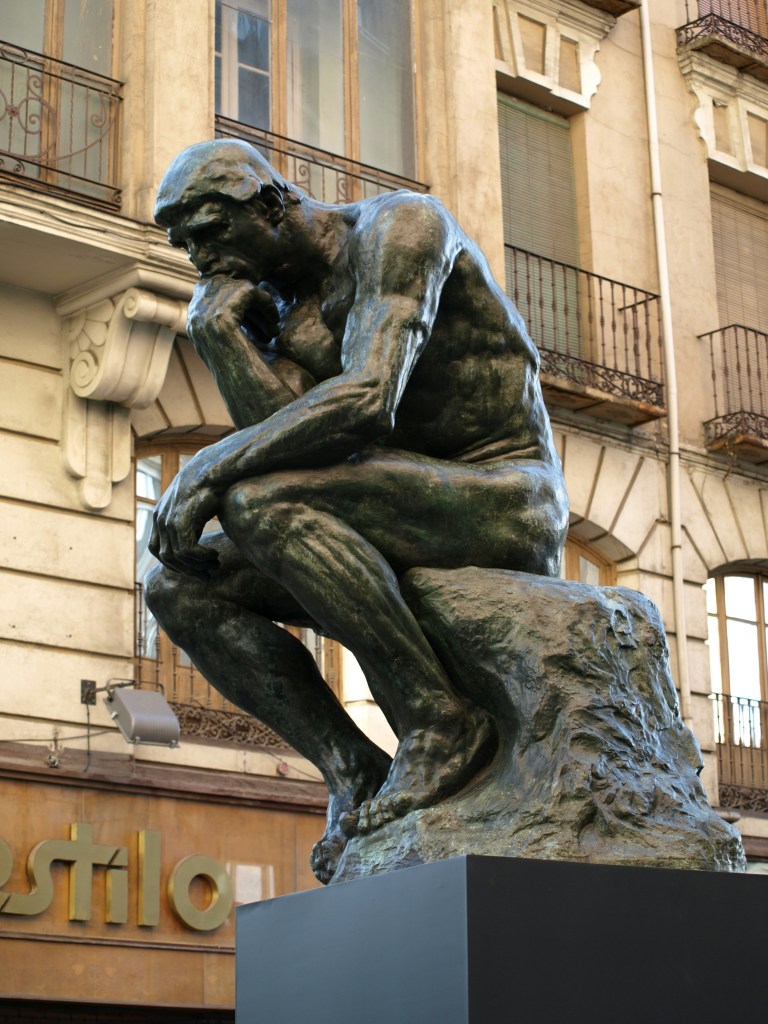

Introversion is often confused with shyness, sadness, depression or social anxiety, but these are distinct traits. We’re no more shy, sad, or depressed than anyone else. We’re contemplative, yes, and if we seem lost in thought, it’s because we are—thinking deeply.

I’ve often been asked why I’m “so quiet.” Need I say that only extroverts ask that question? For years, their persistent curiosity about my reserved nature left me feeling that I should be a little more like them and a little less like myself—at least publicly. More relaxed, more cheerful, more talkative. But explaining that I’m simply quiet always felt futile. Extroverts don’t understand.

And why is it that no one ever asks extroverts why they talk so much? Why must we justify our quietness?

Another misconception is that we dislike talking. We’re not fans of small talk, true, but we love meaningful conversations. We’re not antisocial or misanthropic—no more than anyone else. Some extroverts dislike people and use them to feed their egos, yet their social skills are rarely questioned. Our social needs vary: some of us need very little interaction, others more. But generally, we prefer a small circle of close friends. The word “acquaintance” rarely appears in our vocabulary. What do you do with acquaintances besides chit-chat? And for us, chit-chat is a struggle that non-introverts can’t fully grasp.

We are not broken extroverts, and we don’t need to be fixed.

Introverts need solitude and quiet spaces to recharge their mental energy. Our friendships may be few, but they endure the tests of time, distance, and silence. We can enjoy crowds and noise (I’m obsessed with Monster Track shows, Formula 1 races, and other thunderous events), but afterward, we retreat to our mental and physical sanctuaries to recharge. That’s the key difference: we refuel from within; extroverts recharge externally.

If we can choose (and we rarely can), we will rather work alone than in a team. If there is no option (and often there isn’t), we’ll shrug and team up without too much fuss. Although from my experience, when we work together with extroverts, they tend to talk and brainstorm, while we do the actual work. We hate to be put in the spotlight or when we must introduce ourselves to a group of unknown people. I call those ice breakers ice makers — I freeze out of deep discomfort every time I’m pushed in such situations. Introverts often struggle with public speaking and icebreaker activities, preferring low-stimulation environments.

Of course, this introvert/extrovert classification is not black and white; otherwise, the world would be a madhouse. It’s more like the use of hands: one is dominant, but you need both to tie your shoes. I believe (again, this is my opinion) that, in this regard, my kind is more flexible and adaptable than the extroverts.

If necessary, we know how to be more open even though it’s against our nature, or reliable team players even though we know that we would work faster and better alone. Many of us possess the cognitive ability to learn how to be more social and push through unavoidable gatherings without too much trouble. After all, there is always a chance of meeting one of us in such places, some poor introvert, who would rather be anywhere else than there, yet he/she didn’t have a choice but to come. It’s easy to spot such a soul; you just look at the farthest corners. More than one deep and long-lasting friendship between two introverts has been forged that way.

Show me an extrovert who is capable of being alone, working independently and appreciating the silence of his or her own thoughts.

I don’t know if we are born as introverts or extroverts or if we, during our lives, come closer or farther from each other. It’s possible that the combination of nature, heritage and social environment determines which category we predominantly will fall into, or if we’re going to crisscross the borders or not. I haven’t changed a whole lot since I was a child; if anything, my introversion is more prominent now than before. But so are my cognitive faculties to cope, blend in and accept many aspects of extraversion.

My friends are sparse and precious, and most of them are introverts because it was I who chose them. I have a few extroverted friends as well, and we have great relationships because we complement each other’s personalities. But in those cases, I had been chosen. And I think that what they are to me is not what I am to them. They have one hundred percent of me. I have only a piece of them. Maybe a big piece, but still a piece. I am just one of their countless friends, with certain specifications and purpose, because they need so many others to feel complete.

There is little understanding of “quiet people,” even though we’ve been moving the world since the dawn of humankind. In silence, of course. Solitude, not noise, is a breeding ground for originality and creativity, for art and science; nobody can convince me otherwise. It fuels creativity and innovation—many introverts thrive in quiet environments that foster deep thinking. Unfortunately, and not very logically, today’s society—school, businesses, important institutions—is designed for extroverts and their need for external stimulation. This is the world that worships individualism, not character — the world made for “mighty likable fellows”.

And that’s fine. We don’t care much; it’s not in our nature. I only wish that they could see, or that we could explain to them, that our quiet power is that mighty foundation on which their world stands.

*The title of Susan Cain’s book mentioned at the beginning of this little tribute to my strong and silent kin, “Quiet: The Power of Introverts in the World that Can’t Stop Talking”.

**The lovely definition of true friendship, which I partially quoted, is allegedly by Isabel Allende and it goes, “True friendship resists time, distance and silence.”

***This phrase is also borrowed from S. Cain’s book.

Thanks for this, Jasna, and congratulations on the article being published.

It has taken me a long time to accept that being an introvert is normal. I’m glad for books like Susan Cain’s that promote the idea to readers. On the other hand, I see messages out there that say “It’s okay to be an introvert, but here are some tips for looking like an extravert, because you really have to do that to succeed.” In my working life I noticed that people in higher paid positions spent a lot of time in meetings and talking on the phone. Those whose jobs could be done alone were assumed to be unimportant drones.

I could go on and on, but I won’t. Thanks again for this post!

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thank you for your great comment!

You perfectly summarized the societal attitudes toward introverts. Unfortunately, extroversion is often seen as one of the most important keys to success.

We make them uneasy, that’s why they want us to be more like them. And I find it oddly satisfying.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Your essay speaks directly to me. I need a lot of alone time and thinking time. Being around a group of extroverts for an extended period of time makes me very tired.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you, Liz. I’m glad (but not surprised) that it resonates with you. Same with me – I feel drained after being among extroverts no matter how much I like them. I wonder how they feel after spending time among us. They probably don’t enjoy it either! 😉

LikeLiked by 1 person

You’re welcome!

LikeLiked by 1 person

I’ve read Cain’s book. It was informative. For the longest time I was afraid I didn’t like people. But I love people! I just need quiet, alone-time afterwards to recharge.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I believe we truly and deeply love people, only on an individual level, not en masse. Thanks for reading my post and commenting!

LikeLiked by 1 person