The Forgotten Heroine of Three Wars

She is considered one of the most—if not the most—decorated female soldiers in world military history. She was a veteran of three wars: the First Balkan War (1912), the Second Balkan War (1913), and the Great War (1914–1918).

Yet, outside of Serbian-language sources, there’s little about her online. In the eyes of global powers, small countries often have small histories—histories deemed not worth remembering.

Her name was Milunka Savić, born in 1888. She was 24 when the First Balkan War began in 1912—a conflict between the Balkan League (Serbia, Bulgaria, Greece, and Montenegro) and the Ottoman Empire, aimed at ending Ottoman rule in Europe. To protect her ailing brother from conscription–allegedly–Milunka cut her hair, donned men’s clothing, and took his place.

The First Balkan War ended in May 1913. Just a month later, the Second Balkan War erupted when Bulgaria, a former ally, attacked Serbian and Greek forces over the division of Macedonia. It was during this war that Milunka’s true identity was discovered. Her famed Iron Regiment fought fiercely at the Battle of Bregalnica, one of the bloodiest clashes of the war. They bore the brunt of Bulgaria’s assault, launching counterattack after counterattack. On her tenth charge, Milunka was severely wounded. At the field hospital, doctors discovered she was a woman.

She was offered a transfer to the nursing corps. She refused.

In August 1914, the Great War began. Sergeant Milunka Savić, now commander of the Iron Regiment’s Assault Bomber Squad, fought in around 20 major battles against the enemy.

Wounded nine times, she received Serbia’s highest military honors multiple times, along with the two Legion of Honour and a Croix de Guerre (France), Order of St. Michael (Britain), and Order of St. George (Russia), among others. She was nicknamed the Serbian Joan of Arc. Our Mulan—before we ever heard of Mulan.

Her most recent recognition came from Swedish heavy metal band Sabaton, whose music celebrates wartime heroism. Their song Lady of the Dark tells Milunka’s story. If you have a moment, pin a metaphorical poppy to your lapel in her honour and listen to their video.

After the Guns Fell Silent

Peace was not kind to Milunka. She declined an offer to move to France, choosing instead to remain in her homeland. She worked in a post office. Married, had a daughter, divorced. Adopted and raised three more daughters. She lived in obscurity and died in 1973.

She isn’t entirely forgotten—but she isn’t remembered as she should be. Perhaps that’s what happens when nations have too much history and not enough peaceful time to dwell on it. We tend to remember only the big events and major players.

But, there are countless stories of ordinary–and not so ordinary–people, kept alive not in history books but in memory.

Here are some of them: King Peter I of Serbia, affectionately known among his subjects as “Uncle Pera,” was 71 when he led his retreating army, government, and tens of thousands of civilians through the Albanian mountains to Greece. Albanian Prime Minister Ahmed Esad Pasha Toptani, defying his own government, allowed them passage—saving countless lives.

The king carried a pair of hand-knitted wool socks, entrusted to him by a soldier’s mother. He found the son—but too late. The boy had died of cold and exhaustion. The mother died too, of grief. The king ordered a monument in their memory and kept the socks under his pillow until his death. Some say he was buried in them.

The Great War had the youngest known soldier, Momčilo Gavrić. I wrote about him, a boy who was “adopted” by a passing artillery unit after Austrians slaughtered his entire family. When he was demobilized in 1918, he was just 11 years old.

A Roma trumpeter in the Second Balkan War spied on the enemy, learned their signals, and sounded a retreat on their behalf—causing chaos among Bulgarian troops.

And so on… the endless string of wars and the countless accounts.

My Family’s War Stories

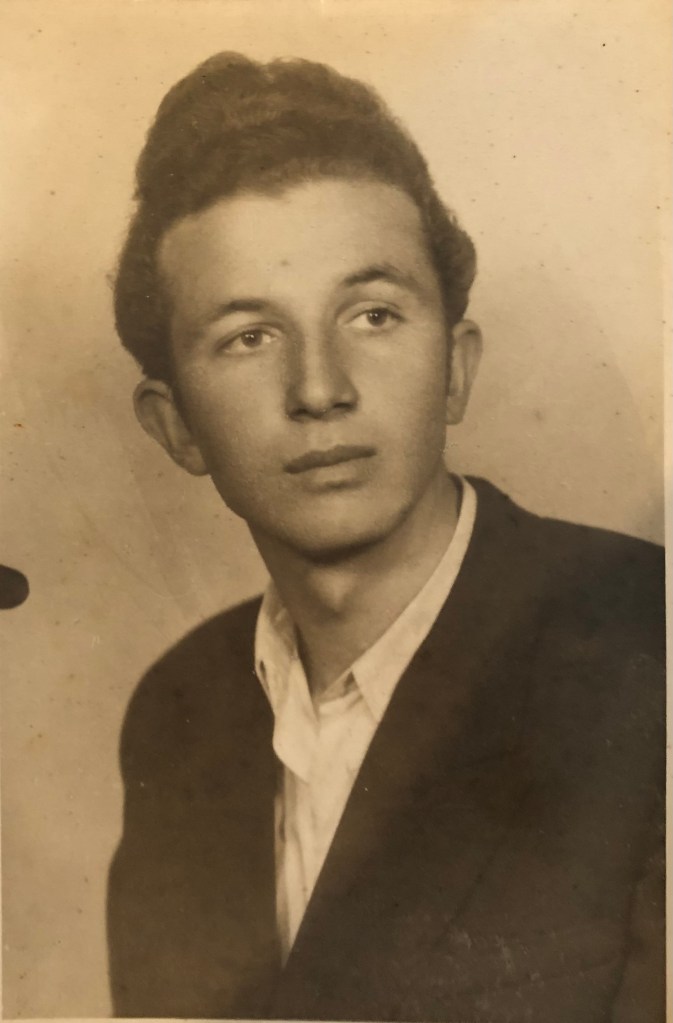

My son’s great-grandfathers fought in the Great War—one was Serbian, another an Austrian—on the same side, under the Austro-Hungarian flag. Both survived. My Austrian grandfather was presumed dead but returned home in 1921 after years in a Russian POW camp and married my Serbian grandmother.

Both my father and father-in-law fought in WWII. My father was 17, my father in-law only 15 in 1941, when he joined the resistance. My husband’s aunt—our family’s own “Joan of Arc”—was demobilized in 1945 as a colonel in the Yugoslav Army. She was 27.

My great-uncle Anton died in Stuttgart during an Allied bombing in 1943. He was a civilian.

My stepfather was just seven years old when Italy occupied his province during World War II. (His father had been mobilized, though.) He remembered the Italian soldiers with surprising fondness—they weren’t brutal and often helped civilians, even sharing food. One Italian soldier gave him the first chocolate he ever tasted. Everything changed drastically to worse after Italy capitulated in 1943 and the Germans took control.

My maternal grandfather was fortunate: he served as an army barber during the war, a role that spared him from the front lines and the bloodshed.

We say that every generation has its own war. My husband and I came here in 1996—after ours.

The Balkans: Beautiful and Troubled

The Balkans are a crossroads of civilizations and religions. The gateway to Central and Western Europe, the cradle some of the oldest civilizations and cultures. A phoenix—prone to self-burning (on rare occasions when there aren’t outsiders with torches), but capable of rebirth. Tragic yet resilient.

In moments of peace, we clean the ruins and start over. We produce Nobel laureates, brilliant scientists, world-class athletes, pianists, artists, architects.

But war visits us too often. In the 20th century alone, some parts of my former country saw five: 1912, 1913, 1914, 1941, 1991. The lucky ones skipped one or two.

Surprisingly, a quarter of this century has passed in peace—fragile, uncertain, but peace nonetheless. Seventy-five years remain to break the record, though. I’m not holding my breath.