What’s wrong with three famous H. K. Andersen’s fairy tales?

A couple of years ago, I wrote a post about a collection of fairy tales I got when I was five, my very first books.

I loved them—particularly some—for their incredible illustrations, which even now, decades later, take my breath away. But story-wise, it was an odd mélange: well-known fairy tales along with obscure ones, simplified children’s classics such as Alice in Wonderland and Peter Pan, Aesop’s and Lafontaine’s fables. Among them were also Hans Kristian Andersen’s literary fairytales, adapted for this collection’s targeted audience–quite young readers, not older than four or five.

I would come back to some stories over and over again, and avoided some others, depending on how they ended. My young mind divided the entire collection into three groups — those with happy endings, those with sad endings, and the fables, which I didn’t care about at all.

Andersen’s tales included in this collection — The Little Mermaid, The Steadfast Soldier and The Little Match Girl — have always been problematic for me. To say that these stories have sad endings would be an understatement. They are depressing, devastating, and heartbreaking: the little mermaid dies, the little match girl freezes to death, and the tin soldier jumps into a fire with his paper doll ballerina.

Not all of Andersen’s fairy tales and stories are so grim. I’ve always loved The Snow Queen, Nightingale, The Princess and the Pea, and many more. But, without exaggeration, I can also state that The Little Mermaid, The Little Match Girl and The Steadfast Soldier scarred me for life.

What do parents tell their kids when they ask why the little mermaid, the soldier and the match girl had to die?

I don’t believe children should be shielded from every unpleasantry of life, including death, but they surely are not going to understand the existential challenges through these tales. I’m almost grateful for Disney’s sanitized interpretation, The Little Mermaid (1989); given the targeted audience, it’s incomparably more sensible.

In Andersen’s story, the Little Mermaid falls in love with a prince whom she saved. As it happens in life, he falls in love with another girl, convinced it was her who saved him. In exchange for her enchanting voice, a sea witch grants Little Mermaid legs and ability to dance, but every step she takes feels like knife stabbing and her feet bleed. That’s not all: the Little Mermaid also wants a human soul, so that she can go to heaven when she dies. To accomplish it, she only needs a true love kiss from the prince.

We all know that this is not going to happen. To reverse the magic, she needs to stab the prince with the knife her sisters sacrificed their hair for, and drip the prince’s blood on her legs to get her tail back, which she can’t do, so she jumps into the ocean, becomes a foam, or something else, with the promise of reaching heaven after 300 years, providing she’s been good. Foam or not, she de facto committed suicide, yet this unforgivable sin in Andersen’s times didn’t bother him a bit.

What the frick! Sacrifice, unrequited affection, prohibited love, punishment for having earthly desires, pain (excruciating, of course), blood, purgatory, uncertain promises of heaven… are these the values this story tries to teach kids? It sounds more like a sermon from a pulpit delivered by an overly zealous priest than a fairytale by a renowned children’s author. Not to split hairs, but there is also ground for some serious criminal allegations: premeditated although not executed murder of an innocent man, possession of a weapon for dangerous purpose (the Mermaid); conspiracy to commit murder and accessories to murder (the sisters and the witch). If you have a legal background, tell me which potential charges I’ve missed to mention.

If The Little Mermaid is heartbreaking, even in its absurdity, The Steadfast Soldier is utterly depressing and even more unhinged. A series of unfortunate events befall on the soldier: he was made with one leg due to the shortage of tin, he falls in love with a paper ballerina (standing on one leg) but believes he’s not worthy of her love, he falls out of the window, his searchers almost find him only to miss him at the last moment, he was put in paper boat and pushed into a sewer, then swallowed by a fish, made it back home only to be thrown in the fire for no apparent reason. Carried by a gush of wind, the ballerina follows him. Once again, children are not spared from obvious religious preaching: the story features the recurrent motifs of inevitable suffering for being different and punishment for very human longing. All our efforts to change our circumstances are in vain. The steadfast, one legged soldier did everything to fight his misfortune, yet he was defeated anyway. We shouldn’t be surprised by this outcome. After all, this world is vallis lacrimarum, valley of tears.

I won’t even go to The Little Match Girl; I’m still traumatized. Dead mother, dead grandmother, a Christmas Eve—the time of giving, sharing, loving yet everyone just passes by the little orphan–cold, snowy streets, the girl’s bare feet as a metaphor for her utter misery; vision or hallucinations she experiences as she lights the matches before she freezes to death. Some Christmas story!

What was its intent? I don’t know; I don’t see it. What’s the message? That there is no place in this world for the unfortunate and unprivileged, like in The Steadfast Soldier. That we shouldn’t try to change it (the Soldier at least tried), but keep lighting our metaphorical matches until we’re out of them? Or perhaps Andersen wanted to encourage children to look around and notice those who lived on the fringe of society? Well, if that was his intention, it sounds as effective as eating everything that is on your plate to help hungry children in the Third World.

People often say that the folktales Brothers Grim collected and originally published are harsh and disturbing. They are, but they didn’t start as children’s stories. They were for adults and their purpose was adult entertainment–after the kids went to bed. Soon after publishing them, disappointed by the sales, the brothers toned them down and republished as children’s books.

The meanings of the authentic folk tales (not watered down retellings) are imbedded in our collective consciousness. Their roots are deep in our past and they’re part of oral tradition. Our subconscious–or our archaic, primal mind, if you wish–understands them even if our rational mind can’t always grasp their meanings. Their goal isn’t (wasn’t) just to entertain children, but to educate them about life. Those intuitive lessons stay with us forever. The scary stuff in fairy tales, many agree, is helping children deal with fears and grow emotionally. It’s not unlike the effect of scary staff in movies or books – the fact that we are allowed to experience fear, discomfort, even dread in a safe and secure environment, without any harm or consequences, is fundamentally healthy and emotionally beneficial. It’s hard to argue with that.

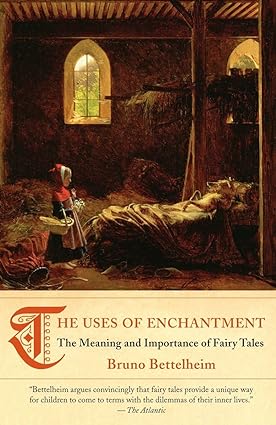

Years ago I read an interesting book that talks about these connections: The Uses of Enchantment: The Meaning and Importance of Fairy Tales (1976) by Bruno Bettelheim. Relying on the Freudian tradition in psychoanalysis, Bettelheim claims that fairy tales help children solve certain but very concrete existential problems such as separation anxiety, oedipal conflict, fears, and sibling rivalries, serving even as rudimentary sexual education, like The Frog Prince. The book later raised some controversies, including plagiarism, but it made lots of sense to me regardless of who the original authors of those theories were.

None of this I’ve been able to find in those three Andersen’s stories. (Oddly enough, it was The Little Mermaid that established his international reputation.) No ties to our subconscious mind or existential conflicts, only religious preaching about suffering, sacrifice, acceptance of the status quo, and punishments without crime. Something is terribly amiss in some of his work, starting with psychological, rational, and logical foundations.

Having these three fairy tales in mind, it would be interesting to know what kind of inner struggles drove Andersen to delve into the darkest, most depressive and utterly hopeless corners of human soul, mold what he found there, and then present that bleakness to children. He was, according to his biographers, a conflicted and complicated soul, but still.

Aside from the religious bull, another obvious common denominator in these three stories are legs and feet. Makes me wonder what an experienced psychoanalyst would make out of it.

Anyone here with a background in psychology?

Interesting about the hands and feet. Yeah, I wonder what a psychologist would think. The Match Girl doesn’t bother me as much as the Tin Soldier and the Paper Ballerina. What a traumatic ending!

LikeLiked by 1 person

I was raised by my grandmother, the most wonderful person in the world, for first seven years of my life. Maybe that’s why The Little Match Girl has always been disturbing to me.

LikeLiked by 1 person

…because at least she had a smile on her frozen face.

LikeLiked by 1 person

… and died happy, so not everything was dark and tragic. “… No one imagined what beautiful things she had seen, and how happily she had gone with her old grandmother into the bright New Year”. This is how the story ends. Leaves me speechless every time.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I was enamored of the original Grimm’s Fairy Tales when I was a kid. They didn’t seem real. As an adult, however, I’ve been horrified to reread fairy tells in which people (or anthropomorphic creatures) are tortured and meet a grisly end.

LikeLiked by 1 person

It’s interesting that some of them sound to me more terrifying now then when I was young. Unlike adults, children seem to be able to separate information from their senses and perceive things differently.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yes, that seems to be the case.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I just looked at “The Little Mermaid” in a collection of stories called The Golden Story Book I’ve had since I was a kid. I remember appreciating the drama of it, and actually wishing the mermaid had killed the prince. 😮 I think as kids we recognize these stories aren’t real so don’t evaluate them the same way.

As for Andersen, in the same book, just before the mermaid story is another by him, called “The Fir Tree.” It’s about a Christmas tree–how wonderful it is to be chosen and decorated, and yes, at the end it’s thrown out and burned. The last sentence says the tree’s life was past, and that’s how it is with all stories. Andersen had a grim view of life, it seems.

Don’t forget that when these stories were first written, even children were more accustomed to those close to them dying. Death was closer to daily life then.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I vaguely recollect The Fir Tree, thank you for reminding me. Some of his stories are very dark indeed, some others are not, or at least they don’t end in total despair. I hate half of his work. Regardless of the time, I’ve always felt there was something sinister in many of his “fairy tales”, as if he deliberately wanted to hurt his young readers. Maybe he was a tortured soul, hence all that suffering, struggle, need for cleansing… or maybe he was just mean.

LikeLiked by 1 person